Introduction to genes

Introduction to genes |

|

Words you must know |

| chromosome /染色体 | ribosome /核糖体 | chromatin /染色质 | nitrogenous bases /含氮碱基 | adenine(A) /腺嘌呤 | guanine(G) /鸟嘌呤 | cytosine(C) /胞嘧啶 |

| thymine(T) /胸腺嘧啶 | uracil(U) /尿嘧啶 | nucleotides /核甘酸 | ribonucleic acid (RNA)/核糖核酸 | enzyme /酶 | mutation /突变 | phosphates /磷酸 |

Related resources for download |

| Download PPT: Reproductive system |

| Download videos: Crach Course: Male |

| Download videos: Crach Course: Female |

| Download videos: Female |

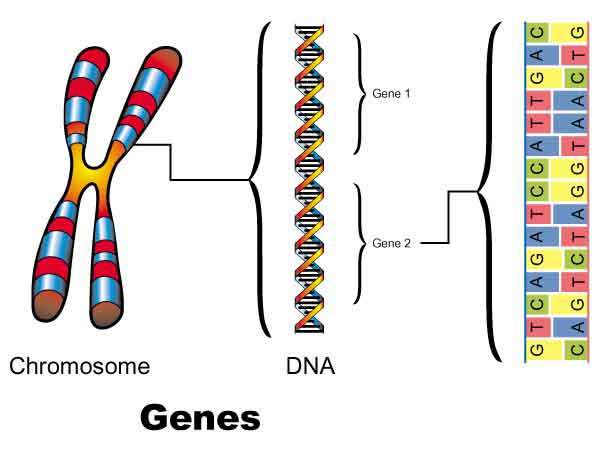

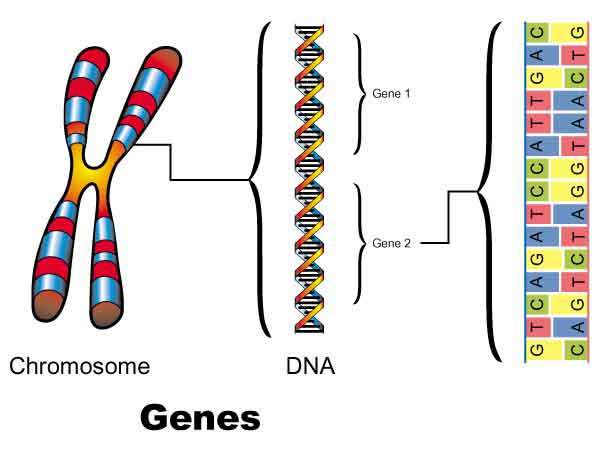

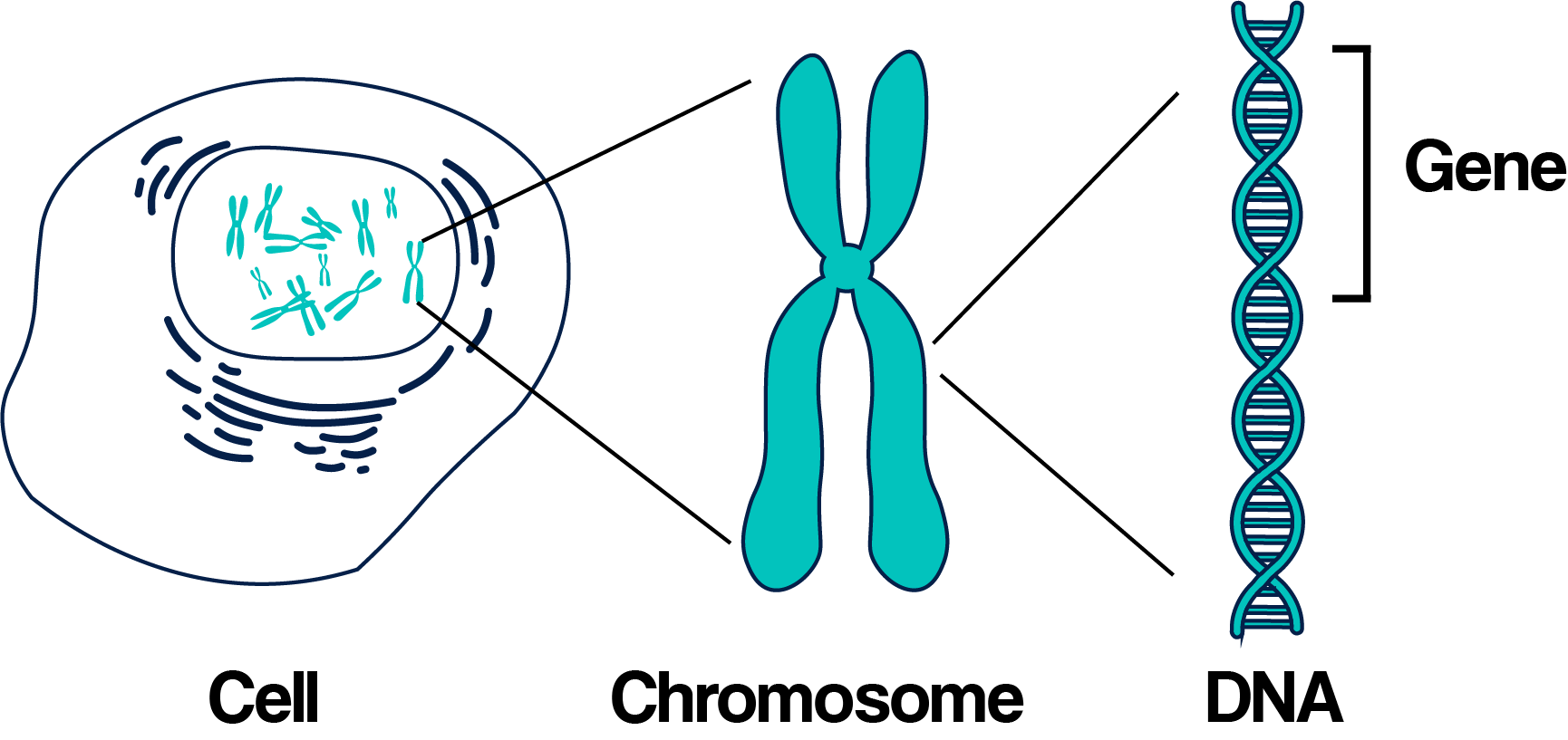

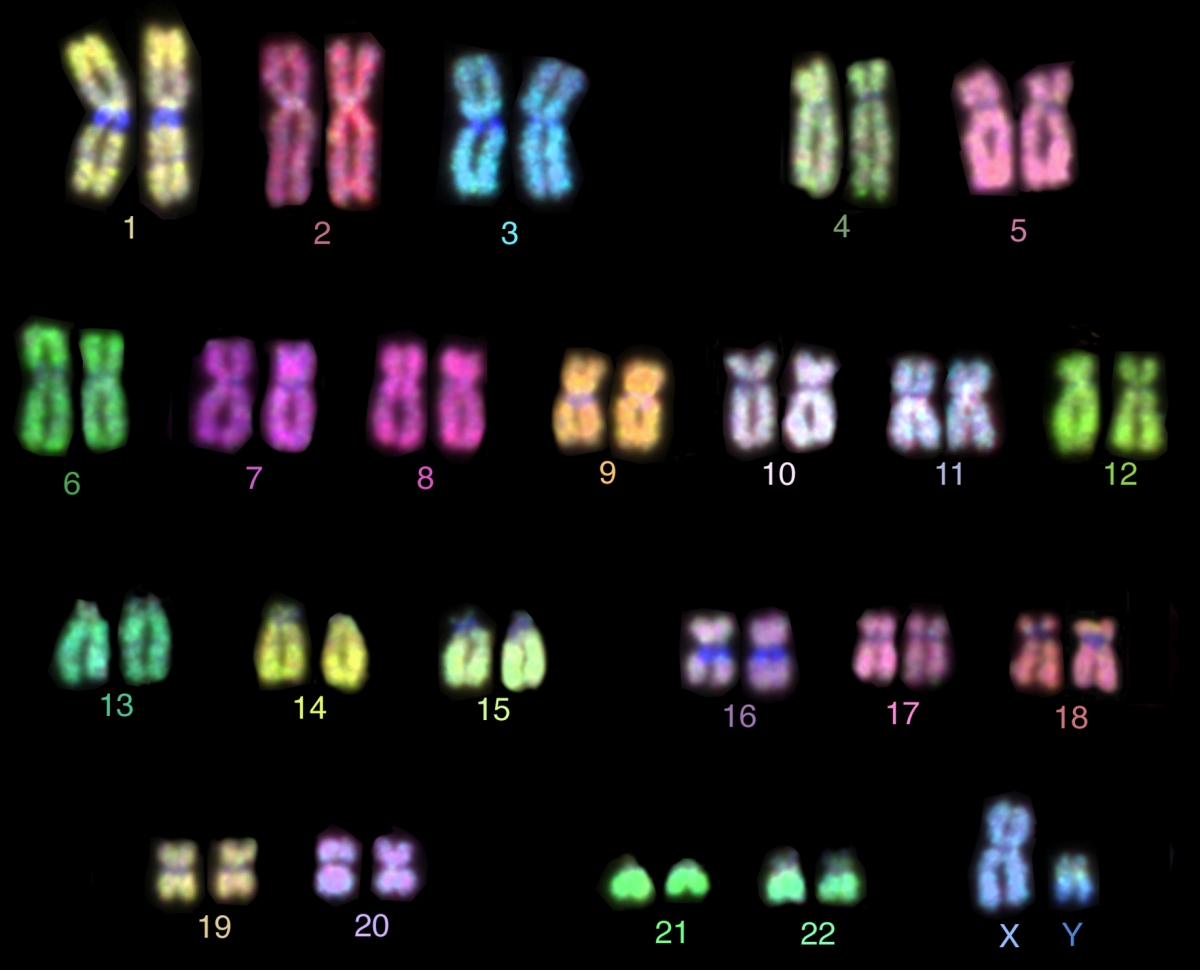

Every cell in the body with a nucleus (a compartment in most cells) has the same complete set of genes. A gene is made of DNA (deoxyribonucleic acid) and is basically a type of genetic instruction. Those instructions can be used for making molecules and controlling the chemical reaction of life. Genes can also be passed from parent to offspring; this is inheritance. Some genes are active ('on') in some tissues and organs but not in others. This is what makes the difference between a liver cell and a lung cell. Genes are turned on and off during development and in response to environmental changes, such as metabolism and infection. "Half of your DNA is determined by your mother's side, and half is by your father. So, if you seem to look exactly like your mother, perhaps some DNA that codes for your body and how your organs run was copied from your father's genes." So close, yet so far. This quote, taken from a high school student's submission in a national essay contest, represents just one of countless misconceptions many people have about the basic nature of heredity and how our bodies read the instructions stored in our genetic material (Shaw et al. 2008). Although it is true that half of our genome is inherited from our mother and half from our father, it is certainly not the case that only some of our cells receive instructions from only some of our DNA. Rather, every diploid, nucleated cell in our body contains a full complement of chromosomes, and our specific cellular phenotypes are the result of complex patterns of gene expression and regulation. In fact, it is through this dynamic regulation of gene expression that organismal complexity is determined. For example, when the first draft of the human genome was published in 2003, scientists were surprised to find that sequence analysis revealed only around 25,000 genes, instead of the 50,000 to 100,000 genes originally hypothesized. Clues from studies examining the genomic structure of a variety of organisms suggest that much of human uniqueness lies not in our number of genes, but instead in our regulatory control over when and where certain genes are expressed. Additional examination of different organisms has revealed that all genomes are more complex and dynamic than previously thought. Thus, the central dogma proposed by Francis Crick as early as 1958 — that DNA encodes RNA, which is translated into protein — is now considered overly simplistic. Today, scientists know that beyond the three types of RNA that make the central dogma possible (mRNA, tRNA, and rRNA), there are many additional varieties of functional RNA within cells, many of which serve a number of known (and unknown) functions, including regulation of gene expression. Understanding how the structure of these and other nucleic acids belies their function at both the macroscopic and microscopic levels, and discovering how that understanding can be manipulated, is the essence of where genetics and molecular biology converge. Detailed comparative analysis of different organisms' genomes has also shed light on the genetics of evolutionary history. Using molecular approaches, information about mutation rates, and other tools, scientists continue to add more detail to phylogenetic trees, which tell us about the relationships between the marvelous variety of organisms that have existed throughout the planet's history. Examining how different processes shape populations through the culling or maintenance of deleterious or beneficial alleles lies at the heart of the field of population genetics. Within a population, beneficial alleles are typically maintained through positive natural selection, while alleles that compromise fitness are often removed via negative selection. Some detrimental alleles may remain, however, and a number of these alleles are associated with disease. Many common human diseases, such as asthma, cardiovascular disease, and various forms of cancer, are complex-in other words, they arise from the interaction between multiple alleles at different genetic loci with cues from the environment. Other diseases, which are significantly less prevalent, are inherited. For instance, phenylketonuria (PKU) was the first disease shown to have a recessive pattern of inheritance. Other conditions, like Huntington's disease, are associated with dominant alleles, while still other disorders are sex-linked-a concept that was first identified through studies involving mutations in the common fruit fly. Still other diseases, like Down syndrome, are linked to chromosomal aberrations that can be identified through cytogenetic techniques that examine chromosome structure and number. Our understanding in all these fields has blossomed in recent years. Thanks to the merger of molecular biology techniques with improved knowledge of genetics, scientists are now able to create transgenic organisms that have specific characters, test embryos for a variety of traits in vitro, and develop all manner of diagnostic tests capable of identifying individuals at risk for particular disorders. This interplay between genetics and society makes it crucial for all of us to grasp the science behind these techniques in order to better inform our decisions at the doctor, at the grocery store, and at home. As we seek to cultivate this understanding of modern genetics, it is critical to remember that the misconceptions expressed in the aforementioned essay are the same ones that many individuals carry with them. Thus, when working together, faculty and students need to explore not only what we know about genetics, but also what data and evidence support these claims. Only when we are equipped with the ability to reach our own conclusions will our misconceptions be altered.  |

Chemical Structure Of GenesGenes are composed of deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA), except in some viruses, which have genes consisting of a closely related compound called ribonucleic acid (RNA). A DNA molecule is composed of two chains of nucleotides that wind about each other to resemble a twisted ladder. The sides of the ladder are made up of sugars and phosphates, and the rungs are formed by bonded pairs of nitrogenous bases. These bases are adenine (A), guanine (G), cytosine (C), and thymine (T). An A on one chain bonds to a T on the other (thus forming an A–T ladder rung); similarly, a C on one chain bonds to a G on the other. If the bonds between the bases are broken, the two chains unwind, and free nucleotides within the cell attach themselves to the exposed bases of the now-separated chains. The free nucleotides line up along each chain according to the base-pairing rule—A bonds to T, C bonds to G. This process results in the creation of two identical DNA molecules from one original and is the method by which hereditary information is passed from one generation of cells to the next. Gene Transcription And TranslationThe sequence of bases along a strand of DNA determines the genetic code. When the product of a particular gene is needed, the portion of the DNA molecule that contains that gene will split. Through the process of transcription, a strand of RNA with bases complementary to those of the gene is created from the free nucleotides in the cell. (RNA has the base uracil [U] instead of thymine, so A and U form base pairs during RNA synthesis.) This single chain of RNA, called messenger RNA (mRNA), then passes to the organelles called ribosomes, where the process of translation, or protein synthesis, takes place. During translation, a second type of RNA, transfer RNA (tRNA), matches up the nucleotides on mRNA with specific amino acids. Each set of three nucleotides codes for one amino acid. The series of amino acids built according to the sequence of nucleotides forms a polypeptide chain; all proteins are made from one or more linked polypeptide chains. Gene RegulationExperiments have shown that many of the genes within the cells of organisms are inactive much or even all of the time. Thus, at any time, in both eukaryotes and prokaryotes, it seems that a gene can be switched on or off. The regulation of genes between eukaryotes and prokaryotes differs in important ways. The process by which genes are activated and deactivated in bacteria is well characterized. Bacteria have three types of genes: structural, operator, and regulator. Structural genes code for the synthesis of specific polypeptides. Operator genes contain the code necessary to begin the process of transcribing the DNA message of one or more structural genes into mRNA. Thus, structural genes are linked to an operator gene in a functional unit called an operon. Ultimately, the activity of the operon is controlled by a regulator gene, which produces a small protein molecule called a repressor. The repressor binds to the operator gene and prevents it from initiating the synthesis of the protein called for by the operon. The presence or absence of certain repressor molecules determines whether the operon is off or on. As mentioned, this model applies to bacteria. The genes of eukaryotes, which do not have operons, are regulated independently. The series of events associated with gene expression in higher organisms involves multiple levels of regulation and is often influenced by the presence or absence of molecules called transcription factors. These factors influence the fundamental level of gene control, which is the rate of transcription, and may function as activators or enhancers. Specific transcription factors regulate the production of RNA from genes at certain times and in certain types of cells. Transcription factors often bind to the promoter, or regulatory region, found in the genes of higher organisms. Following transcription, introns (noncoding nucleotide sequences) are excised from the primary transcript through processes known as editing and splicing. The result of these processes is a functional strand of mRNA. For most genes this is a routine step in the production of mRNA, but in some genes there are multiple ways to splice the primary transcript, resulting in different mRNAs, which in turn result in different proteins. Some genes also are controlled at the translational and posttranslational levels. Gene MutationsMutations occur when the number or order of bases in a gene is disrupted. Nucleotides can be deleted, doubled, rearranged, or replaced, each alteration having a particular effect. Mutation generally has little or no effect, but, when it does alter an organism, the change may be lethal or cause disease. A beneficial mutation will rise in frequency within a population until it becomes the norm. |